Your SaaS vendor's opinion is not your strategy

Why goal-oriented, semantically guardrailed enterprises will replace the workflow-oriented businesses that SaaS created.

The way most enterprises operate today was not designed by their leadership. There’s no way, given a blank cheque and a clean slate would leaders build a business operating model in the way it’s done today. The operating models that we see in enterprises are designed by their software vendors. A “Conway Capture” has occurred. Similar to Regulatory Capture, the enterprise’s operational design ends up serving the assumptions an opinions of the vendor it was supposed to be buying capability from.

Salesforce dictates an opinion about how sales should work. SAP encodes an opinion about procurement. ServiceNow enforces an opinion about service management. HubSpot decides an opinion about marketing. Each platform ships with a set of assumptions about what a business process looks like, what sequence it should follow, what data matters, and what "good" means. Enterprises, through necessity, have adopted these opinions pretty much across the board. This is not because they were the best expression of how any individual business creates value, but because the alternative was prohibitively expensive.

The collective consciousness of the industry has coined this as "best practice." The reality is that it's an average across an industry, built to serve thousands of customers, which means built to serve none of them precisely. Pure generalisation across a very broad base. Every customisation project, every middleware integration, every multi-year programme to "make SAP work for our business" is a symptom of the same underlying problem: enterprises fighting against the opinions embedded in their own tooling.

For fifteen years, that fight was worth having because the SaaS bargain was rational. The opinion came bundled with genuine capability, and the cost of unbundling them was higher than the cost of conforming.

I’m going to show that this equation has now inverted.

The build-vs-buy inversion

For a long time it’s fair to say that building software for business operations was slower. Certainly more capital-intensive, and therefore more risky than buying it. Then came SaaS. It was the faster, safer option. Even if you had to accept the vendor's opinion about how your business should operate you did so in exchange for speed to deploy and the guarantee of a predictable cost. Delegating the risk onto a third party was an added bonus. You might have felt unclean doing this, but the trade-off held because bespoke software demanded large engineering teams, long timelines, and significant upfront investment.

Then, welcome GenAI! This paradigm shift change has collapsed the premise of buy over build. Because of more and more capable coding agents, the marginal cost of building custom software has fallen so dramatically that teams now have to re-evaluate tools that were previously "obvious buys." Or “Best Practice” if you will. When 80% of a workflow tool can be assembled through natural language, your business language or even brand specific language to boot, and all generated on demand, a recurring subscription model starts to feel less like efficiency and more like tactical compromise or even a bit of a racket.

This isn't some hypothetical point. As a bit of internal R&D, I recently built from scratch (or more accurately, a relatively formal specification) a fully featured resource management tool for Valliance in under a week (Aside: it’s incredible to me how the tools can now finally keep up with our creativity). I retrieve the data from the company's project and people management systems, HubSpot and Microsoft 365 respectively. The reason we built it is that we wanted something that it's aligned to a Valliance specific value-oriented commercial model rather than the classic time-and-materials assumption that many if not all off-the-shelf PSA and resource management tool bakes in. That’s what makes it unique. Even a year ago, that would have been a procurement exercise, a vendor evaluation, a compromise on how the tool expects a consultancy to operate, etc, etc ad nauseum. Instead, it was a week of fun and a tool that reflects exactly how our business runs. In fact, we’ve been able to iterate many times to get to what we need and we’re still saving time in the process and that product development cycle is not even our core business.

That experience is becoming common. The build-vs-buy equation is one that has shifted fundamentally and has now structurally inverted for an entire category of software. Middleware, thin-wrapper SaaS, and workflow tools that sit between systems of record are particularly exposed in this new paradigm. The subscription model survives where it delivers genuine, hard-to-replicate capability. It doesn't survive where it's primarily selling an opinion about how work should flow. The UI is particularly vulnerable.

But the cost collapse is the enabler, not the destination. Something more fundamental is changing.

The goal of moving away from Workflows

When it comes to business operations, workflows are the name of the game. Handing off one work packet from one human to the next with some either codified heuristics governing that hand off or maybe tacit knowledge in the team dictate how that works gets defined and moved forward. This workflow orientation has not been adopted because it’s optimal model for how a business should operate. I don’t think I’ll find anyone who’ll argue with me there. It’s because the SaaS platforms that run those businesses are workflow-oriented. The platform imposes its structure, and the organisation conforms. Over time, the distinction between "how our vendor thinks we should work" and "how we work" disappears entirely. The opinion becomes invisible. It feels like the natural order.

Nope. It’s not. Not in the face of new technology. It's an artefact of a technological constraint that is now dissolving.

This is such an exciting time to be a technologist. As reasoning AI and agentic architectures mature, an entirely different operating model becomes viable: the goal-oriented enterprise. Disruption at the very core of the Enterprise is now a reality. Rather than encoding business processes as sequences of steps implemented in SaaS platforms, triggered by events, and governed by vendor-defined rules, the enterprise can legitimately define its own outcomes aligned with its own specific needs. What could the goals be? Well, that’s a question of your own creativity and where you need to take your enterprise and how. So "Optimise trade promotion effectiveness across Northern European markets", "Reduce claims processing time while maintaining regulatory compliance”, and "Reallocate construction equipment across active sites to minimise idle time" all become valid and achievable goals that are no longer constrained by the generic software that used to run businesses. Intelligent agents with access to systems of record, domain-specific APIs, and a semantic model of the business determine how to achieve that goal. The execution path isn't pre-encoded in a vendor's platform. Your agents will take the goal and reason against it, validated it against the enterprise's own ontology, and execute it through API-level capability consumption. I almost can’t believe I’m able to type these words.

This distinction changes what software needs to be. In a workflow world, you need applications comprised of bundled UI, logic, and data, all sold as that most un-consumer friendly model called a subscription.

In a goal oriented world, you need three things: systems of record that encode truth, APIs that expose capability, and a semantic layer that provides meaning and guardrails.

The application layer, as SaaS currently sells it, becomes unnecessary. (The eagle eyed amongst you will have noted that you still will need a subscription for the LLMs etc, but I’m choosing to accept that as foundational because of its flexibility in this context)

This pattern is already being proven in production. Thomas Cavanagh Construction, a large-scale construction firm, replaced fragmented traditional systems with an integrated, ontology-driven platform built on Palantir Foundry - https://blog.palantir.com/revolutionizing-construction-e37cba735796. Workforce management, equipment orchestration, and operational coordination were unified under a single semantic architecture, deployed to over a thousand employees. The result was operations that could scale with business growth without proportional increases in complexity. You can accurately conclude that this is precisely because the system was built around how Cavanagh actually operates, not around a SaaS vendor's generalised opinion of how construction companies should operate.

The Cavanagh example matters not because Palantir is the universal answer, but because the architectural pattern is generalisable: unify around an ontology that encodes your business meaning, consume capability through APIs, and let intelligent systems orchestrate toward goals. The specific technology stack is secondary. The operating model shift is primary. And this reinforces my point earlier about subscriptions of the building blocks and not the opinionated application being the model of choice.

Everyone’s got an opinion. Not everyone’s opinion is worth listening to.

I feel I’ve laid down what the trade off that enterprises were willing to accept was. They were willing to adapt their operating model to align with the genericity of the software vendors application layers. If genericity was the trade-off that was accepted, I feel it’s only fair to examine what that trade-off actually costs.

Naturally, every SaaS platform is built on assumptions. Granted, those assumptions are borne out of years of analysis and subject matter expert input. the software wouldn’t be successful otherwise. When I say assumptions, I mean that Salesforce, for example, assumes your sales process follows a pipeline model with stages, probabilities, and a handoff to account management. Or SAP assumes your procurement follows a requisition-to-payment flow with specific approval hierarchies. These assumptions are encoded deep in the product. That means those assumptions manifest in the data model, and the UI, and the reporting, and the integrations, and, and, and. They're not easily overridden and when you have to, you incur a certain debt in your organisation.

Of course, your enterprise operating model might tally closely with the software vendor opinion. It’s the generally accepted modus operandi after all, and when those assumptions align with how your business creates value, the platform is a genuine accelerator. When those assumptions diverge, you're paying a subscription to be constrained and constrained at a macro level with little room for manoeuvre. And the gap between the vendor's assumptions and your operational reality tends to widen over time as businesses evolve and SaaS platforms calcify around the opinions they shipped with.

Reconsider our own internal R&D built resource management example from above. Every off-the-shelf resource management tool I have evaluated in the past, and I’m sure a lot of you recognise this, assume a time-and-materials commercial model because that's the dominant model in professional services. Supply is often predicated by demand after all. However, the Valliance business is does not operate that way. Rather than bending our operations to fit a vendor's assumption, and paying them a monthly fee for the privilege, and then spending months configuring around the misalignment, we were able to build a tool that reflects how we actually create value. In under a week. That still astonishes me. The cost of conforming to someone else's opinion now exceeds the cost of specifying and building your own.

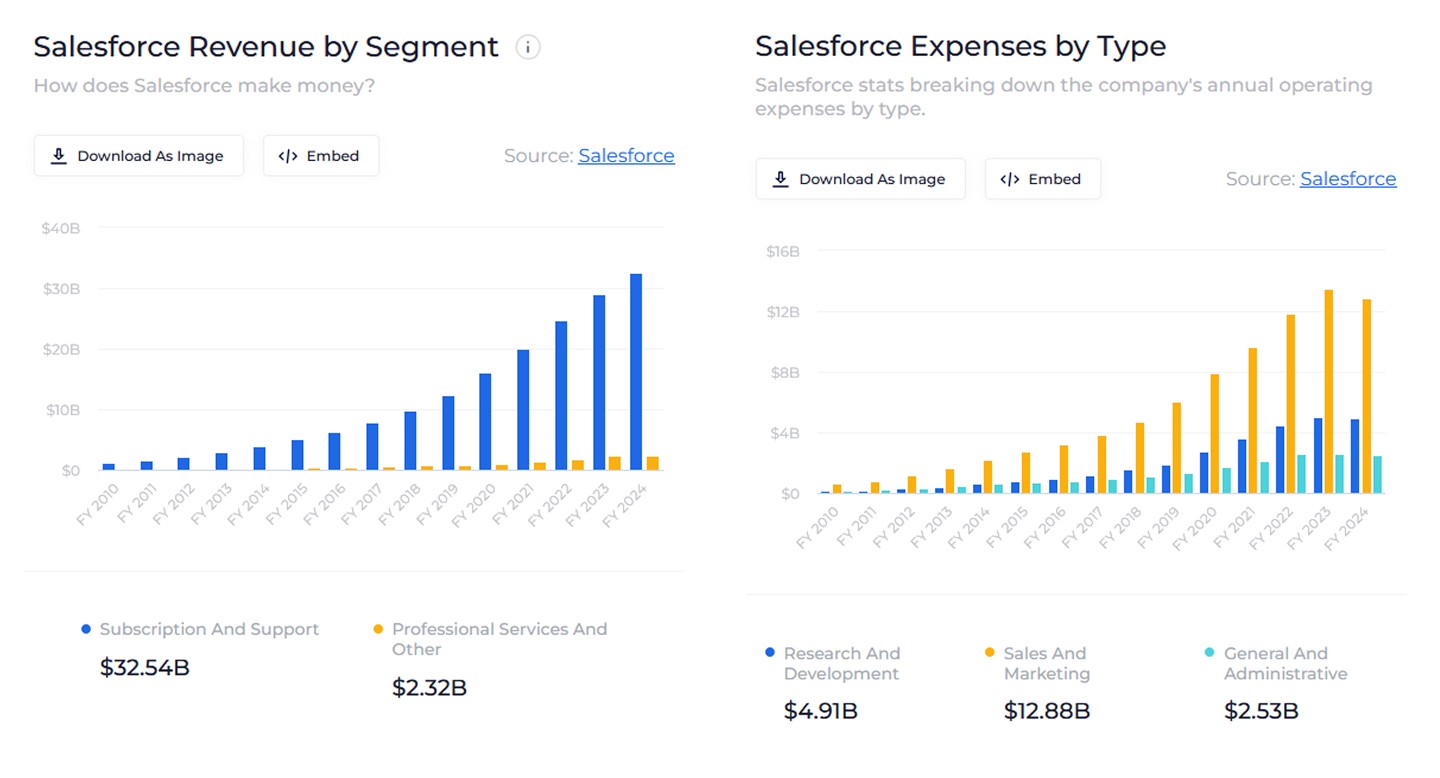

Naturally, it’s to be expected that SaaS vendors pour enormous resources into reinforcing the idea that their opinion is the right one. they have a business to grow and run. Salesforce spent roughly $12 billion on sales and marketing in their 2024 fiscal year. That equates to around a third of total revenue. That spend goes toward sustaining the belief that their workflow is the correct one for your business. The question CIOs need to ask is whether the value they're extracting from a given platform is primarily the capability (which could increasingly be consumed via API) or the workflow opinion (which may actively constrain how their organisation creates value).

This isn't an argument for ripping and replacing overnight. That would be a very challenging position to take. CIOs who've just signed significant renewals haven't necessarily made the wrong call. Time will tell. But those contracts are, and this is something I’m more and more sure on, tactical decisions, not strategic ones. The question is whether the architecture they lock you into will stand the test of time as reasoning AI makes goal-oriented operations viable. That question is rhetorical in my mind. I can’t see any other outcome, frankly. SaaS vendors are going to have to evolve to survive the agentic shift. The ones currently investing in API-first architectures and separating capability from opinion are positioning for what's coming. The ones doubling down on workflow lock-in are building on sand.

APIs as the currency of the future

I really like this sentence; APIs are the currency of the future. I have a rich history in the composable and MACH world and I know the benefits of decomposition in an enterprise context. But the question I ask myself is: If SaaS is decomposing, what persists?

APIs survive because they separate capability from opinion. An API exposes a function without prescribing when, why, or in what sequence or circumstance you should invoke it. That's precisely the interface that intelligent agents need: raw capability that can be composed according to the enterprise's own goals, governed by its own semantic model. The semantic model is doing some very heavy lifting here. Without it. With simply letting an AI loose in your operating model. Well, that way leads to utter chaos. The semantic layer imposes the requisite guardrails to mitigate this chaos.

I’ve touched on this concept of the goal oriented enterprise. One that has direction and the ability to realise that direction unconstrained by opinionated workflow. The software that’s needed to enable and empower this goal-oriented enterprise becomes a catalogue of capabilities exposed as APIs, orchestrated by agents that reason about how to achieve defined outcomes, and governed by a semantic architecture that encodes the enterprise's specific meaning, constraints, and objectives. The SaaS subscription was paying for capability bundled with opinion. The API strips the opinion out and lets the enterprise supply its own. The added bonus that we’ve not even discussed is the fact that all this functionality is co-located. It’s removing a common complaint of the multi-SaaS operating model of a swivel chair problem. No more doing a bit of work in one platform only to hand off to a second system to move the work packet forward.

How enterprises will be evaluating their software estates will evolve with this shift. The question shifts from "which application best fits our needs?" to "which APIs give us the most flexible, composable access to the capabilities we require?" I’m happy to report that user seats, feature matrices, and workflow templates become metrics of a bygone era. API quality, data portability, integration depth, and composability become the things that matter.

There are vendors that recognise this and are already restructuring. However, those that dogmatically stick to their guns will very swiftly find their workflow layer bypassed. The beauty of it all is that it won’t be a competing vendor that will depose them. It will be the enterprise's own agentic infrastructure consuming the capability directly and routing around the opinion. Wonderful!

But… you can’t simply ‘Vibe’ an Operating Model

Dear reader, it would be ridiculous to think that what I mean is completely just in time compute. You’d rightly challenge the premise at this point. If goal-oriented operations rely on agents reasoning about execution paths, doesn't that imply regenerating solutions from scratch every time? That's computationally absurd. Token costs, latency constraints, and the sheer energy required make on-the-fly generation impractical at enterprise scale. Algorithmically reproducing work every single time makes sense for small constrained workloads, but for decisions and goals requiring multiple systems and complex reasoning, that’s going to hurt in many ways and places, not least of all your pocket.

That ‘just-in-time’ compute, and what I mean by that is writing code on the fly for every business action, discarding it, and regenerating it next time. When articulated like that is never going to work today, and may never work for latency-sensitive operations ever no matter how advanced the tech becomes. You can't wait for code generation to add an item to a cart. You can't regenerate a supply chain optimisation model from first principles every time a shipment is delayed.

The resolution lies in what might be called a learning layer. A memory layer that offers a happy medium between pure on-the-fly generation and rigid SaaS workflows. When an agent successfully resolves a goal, the execution path gets recorded as a decision trace. The reasoning that resulting in the successful solution as codified for use next time a similar goal is needed. Over time, the system accumulates an institutional memory of how the enterprise solves its specific problems, optimised for its specific constraints.

I think it’s obvious what the difference is here from a SaaS workflow and that’s ownership. These patterns belong to the enterprise, not to a vendor. They evolve as the business evolves. They're governed by the enterprise's own semantic architecture, by my favourite concept at the moment, the ontology that defines what terms mean, what constraints apply, what rules must be followed, what compliance requirements must be met. The guardrails are yours, not someone else's generalised approximation.

This is what "semantically guardrailed" means in practice. Agents don't operate in a vacuum. They operate within a framework that encodes the enterprise's own rules, validated against its own definition of correct. The framework provides the structure that SaaS workflows used to provide, but it's specific to the enterprise rather than generic to an industry.

Where moats move

You may be surprised to learn that I hadn’t heard of the concept of a moat in business terms until recently. But it makes a lot of sense. In this context, if the application layer is being hollowed out, where does defensible competitive advantage end up?

Code alone is no longer differentiation. When software can be generated on demand, the act of writing it ceases to be a moat. Competitive advantage shifts to four places.

Proprietary data. The information that is uniquely tied to an enterprise. This can include customer behaviour, operational telemetry, domain-specific training data and more. This becomes more valuable as the systems that consume it become more capable.

Deep domain ontologies. Of course. The semantic layer that maps business meaning to capability is the new competitive infrastructure. Two enterprises consuming identical APIs but governed by different ontologies will operate very differently. The ontology encodes how your business understands itself, and how it constrains action. That intellectual property is hard to replicate because it's the nuggets of understanding that describe institutional knowledge all of which took years to accumulate.

Hard-to-replace integrations. There will be instances that differentiate a business through connective tissue to underlying third party or bespoke systems of record. These deep, connections to sources of truth that have probably taken years to establish and validate in regulated industries, of course these will remain genuinely sticky. It’s relatively easy to compose and orchestrate an API. The trust relationship that allows you to write back to a core banking platform will take a while to establish.

Business model innovation. When the cost of building software falls, the ability to experiment with new commercial models, new service delivery patterns, and new ways of creating value becomes a differentiator in itself. The enterprises and partners that can move fastest here gain compounding advantage.

For SaaS vendors, the implication is pretty conspicuous. The survivors will be the ones that recognise their real asset is the API, not the application, and restructure their business model accordingly. The ones that cling to the bundled workflow-plus-opinion model will find themselves bypassed by enterprises that no longer need the bundle.

So what?

I can spend all this time waxing lyrical about the death of SaaS and the rise of the semantic layer, autonomous agents and the Enterprise OS. But what should you, dear CIO reader, do next? How do you protect and take strategic advantage?

Audit your SaaS portfolio for opinions. Categorise each tool by whether you're subscribing primarily for its capability or its workflow opinion or even UX. The former may survive as API-first services. The latter is the category to go into your cross-hairs.

Invest in your own semantic architecture. The enterprise ontology is the governing layer of the agentic enterprise. Without it, you swap SaaS vendor lock-in for AI chaos. This is the foundation that makes goal-oriented operations achievable rather than theoretical.

Reframe procurement from "best application" to "best capability API." Evaluate vendors on API quality, data portability, and composability. User seats and feature matrices are metrics for a model that's running out of time.

Start small with goal-oriented pilots. Pick a domain where the SaaS workflow is visibly constraining. A smell to look out for is a highly customised product. Here you can test whether a goal-oriented, agent-driven approach delivers better outcomes. Valliance can help here, of course - finding valuable outcomes and going after them is what we do.

Pressure your incumbent vendors. Ask them what their API-first strategy looks like. Ask how they're separating capability from opinion. It’ll be obvious which vendors are forward looking and which are trying to maintain a legacy status quo.

The bottom line

We are witnessing the defining architectural shift of the decade: the move from a workflow-oriented to a goal-oriented enterprise. To get there, you don't need another seat-license or a shiny new dashboard. You need a semantically guardrailed agentic operating system. This is an operating model that acts on your goals instead of just tracking your tasks. SaaS vendors gave you the tools to survive the last decade. It’s your own owned intelligence that will define the next one.

SaaS is dead! Your opinion is the one that matters now.